As organisms we are easily identifiable.

Contained by the very skin in which we find ourselves, we hardly change. Yes,

we grow older. Yes, we learn. Yes, we become more mature. We adapt and

integrate and assimilate and make of our inner world a more complex organism,

while perhaps simultaneously coordinating with our outer worlds as a simple

order of constructions. We go to work. Cook. Sleep. And make do. Yet few, like

caterpillars, are entirely metamorphic.

Trumpean pronouncements of "building a wall,"

and the Brexit isolationism are symptomatic of the fears that wall us within.

We hardly can expand into other realities. Like maggots, or fruit flies, bees

or wasps or flowers, we find ourselves identified by our species. Like rats or

bats or dogs or cats; like horses or dolphins or whales, we are self-contained

within the very molecules that go toward making our identity. Evolution is very

slow. It takes several millions of years to make a man from a monkey. It took

many millions of years for an elephant to arise from the rock rabbit. We find

Neanderthal or Rudolfensis or Erectus identities and traits deep within our

ethnic genes. We trace our ancestry online and sign in to DNA testing all in a

search for our origins, all in the interest of discovering the far flung shores

to which we owe some allegiance, some badge of identification; albeit solipsistically.

So the kilt gets replaced by Romania. Or the rice-paddy-hat gets supplanted by

a bowler. We are surprised that we are not really German. The Irish in us come

out. After all, we want a sense of 'true' identity, at last, on which we may

hang our hat.*

But the faults in my analogies in the above lie

in my not championing the evolution of the individual. There is a natural

tendency to presume that all elephants (in the room) materialized

simultaneously: Poof! That one day we were apes, and the next day not. That

Neanderthals suddenly, on April first, in the year 2 million BC, woke to find themselves

more intelligent and humanoid than ever before, as though a Quantum Leap had

taken place: "Everybody in the pool; last one in is a rotten egg!"

Remember those games? Remember the strictures and the acculturation of how to

advance in society, the adoption of language, identity, dress, religion, and

traditional habituations to which you yourself became inured? We identify quite

readily with 'the group", even though we may be urged to be at the

forefront of it. Yet the fault-cracks in our collective-composite are created

by the evolution of individuals, until each finds new community, coming out of

the closets of self containment. Indeed, not all closets are kept closed by

others.

A friend wrote: "Hello Richard, Firstly, I

would like to congratulate you on your acting. You were good. (Indeed, one

emotionally touched reviewer wrote: "The best acting seen in 20 years of attending

Victoria theatre." Another wrote: “Incredibly powerful and moving.”) But

we became friends because we were honest with each other, that was our bond,

and I know that is what you would expect from me now. So let me say that while

you were good, you were not stretched. It was as if you pulled on a familiar

piece of clothing, an overcoat that felt comfortable on you, that was safe. You

knew which button was loose, where the hem needed stitching, where the stain

was that wouldn't come out. It felt agreeable. But I would like to have seen

you pushed into the red zone, because that is where the creativity lies. We

would have seen magic, my friend. You did the best you could with the material,

but the play was dated. We have seen and heard this all before. The jokes were

weak, the dialogue banal, the character development obvious. It was not raw,

not edgy. And we're dealing with life and death mate! But I'm glad I saw it.

Thank you for inviting me."

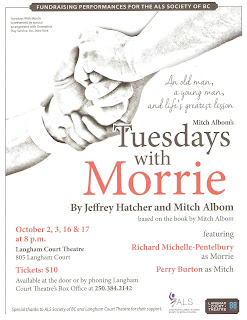

Yes, we are contained by the scripts we are

given, walled within. (I wonder what Mitch Albom, the author of Tuesday's with

Morrie, would think of my friend's critique?) Yet as Morrie himself asks,

"Are you at peace with yourself? Are you trying to be as human as you can

be?" Yes, it is one thing to exercise being "raw and edgy," to

suit some, but also at the same time to be, as Morrie would have it, "filled

with light." Or do we remain year after year, as individuals, as an

identifiable organism, unscratched at the core, carefully closeted, and perpetually

walled within?

* See: Sapiens, A Brief History of Humankind, by Yuval Noah Harari.