Broken, we can never be whole. The cracks can

show. Especially under duress. “Just who do you think you are?” can resonate

down the decades. We can poison ourselves with our past. We can so easily be

hamstrung, hobbled, hurt.

Overcoming childhood insufficiency can be the

worst of it. Little girls are demeaned by boys, by parents, by others. Little

boys too. Like atavistic swimmers, all hoping to reach the edge ‘first,’ there

is little of compassion for (let alone consciousness of) others. It becomes a

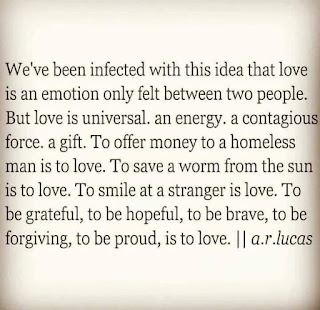

learned thing; we are taught not to step on ants. Gratitude to those who teach

‘love,’ gets profound.

It is thinking about our thinking that

enlightens us. Victim, or victorious, that which was the past can debilitate, or temper our metal. And

although we each are influenced by all those around us, ‘good,’ or ‘bad,’ (according

to The Good Book, to steal from Tevye’s performance in ‘Fiddler on the Roof’), in

the sum of it all, what one makes of one’s life, along the way, is actually up

to oneself. Indeed, one needs think about one’s thinking.

That’s the rub. We are so easily given to

blaming others, or even relying on an ‘Other,’ that such qualities of

‘Self-Reliance,’ and ‘Self-Actualization,’ (let alone ‘Independence,’) are

relinquished into the purvey of our acculturation. Thus it is that there can be

a perpetual ringing of bell-curves in one’s sensibilities. At each juncture of

one’s paradigm shifts (or not,) there is the sense of being an outlier, leaving

an old perspective, until absorbed by the ‘kismet’ of others into yet more and

more acceptance of what once appeared surreal.

In, ‘ADMISSION, a Story Born of Africa,’ Adam

Bradford encounters extraordinary challenges. Given the physical and emotional

abuse perpetuated by a family who do not understand his gifted nature; given

the page-turning adventures among lethal snakes; a child-snatching crocodile;

attacking baboons; a marauding leopard; his having to shoot his beloved pet

donkey; and given the racially charged threats, subsequent murders, and the

political capitulation of Northern Rhodesia into Zambia (1974); for Adam there

is an ‘otherworldly’ quality to his life that (unless in some measure personally

experienced by others,) can indeed appear surreal.

His reader, one trusts, can relate to the

secrets he is forced to keep. His reader, one trusts, can relate to the

necessity to surmount physical pain, emotional difficulty, and inordinate

challenge.

But in relating his unusual story, Adam realizes

that the sheer gauntlet of challenges can hardly be de-rigueur, for most. Thank

goodness. It is his teenage years that become all the more remarkable. His illicit

and interracial affair could prove lethal. His countenancing an abusive uncle

results in extreme hardships. His gainsaying the church gets him whipped. His

escape to a boarding school results in yet more secrets to keep, and when

graduated, and a conscript in the South African Army, he needs take control of

his future, let alone be a victim of the past.

We turn the page to a New Year. We celebrate the

old, learn from the past, and venture into a relative unknown. Some of us are

comparatively secure. We have loved ones near enough. We do not necessarily

feel geographically displaced. We have positions in society, welfare sufficient

to our means, and friends and family, and are relatively fortunate. (Yes,

despite it all, there are those in dire distress, near and dear.) Yet we are

not necessarily victims of our past, unless ‘pushed’. Oh, certain things can ‘set

us off.’ Most usually, they are the things that result from our perceptions

during our upbringing. And thinking about our thinking, indeed, can prove not

only a necessary thing, an immediate thing, but an enduring thing. Accordingly,

adjustments are, consciously, made. After all, each year may indeed be ‘new,’

but so is each moment.

Or do we declare ourselves, ‘always,’ poisoned

by our past?